The most miserable department store in England.

The Victorian cultural necessity of mourning has never failed to capture imaginations. As rules and regulations as to what one should wear, how one should act and what one could do were so closely enforced, businesses soon facilitated and ‘cashed in’ on this burgeoning social wave.

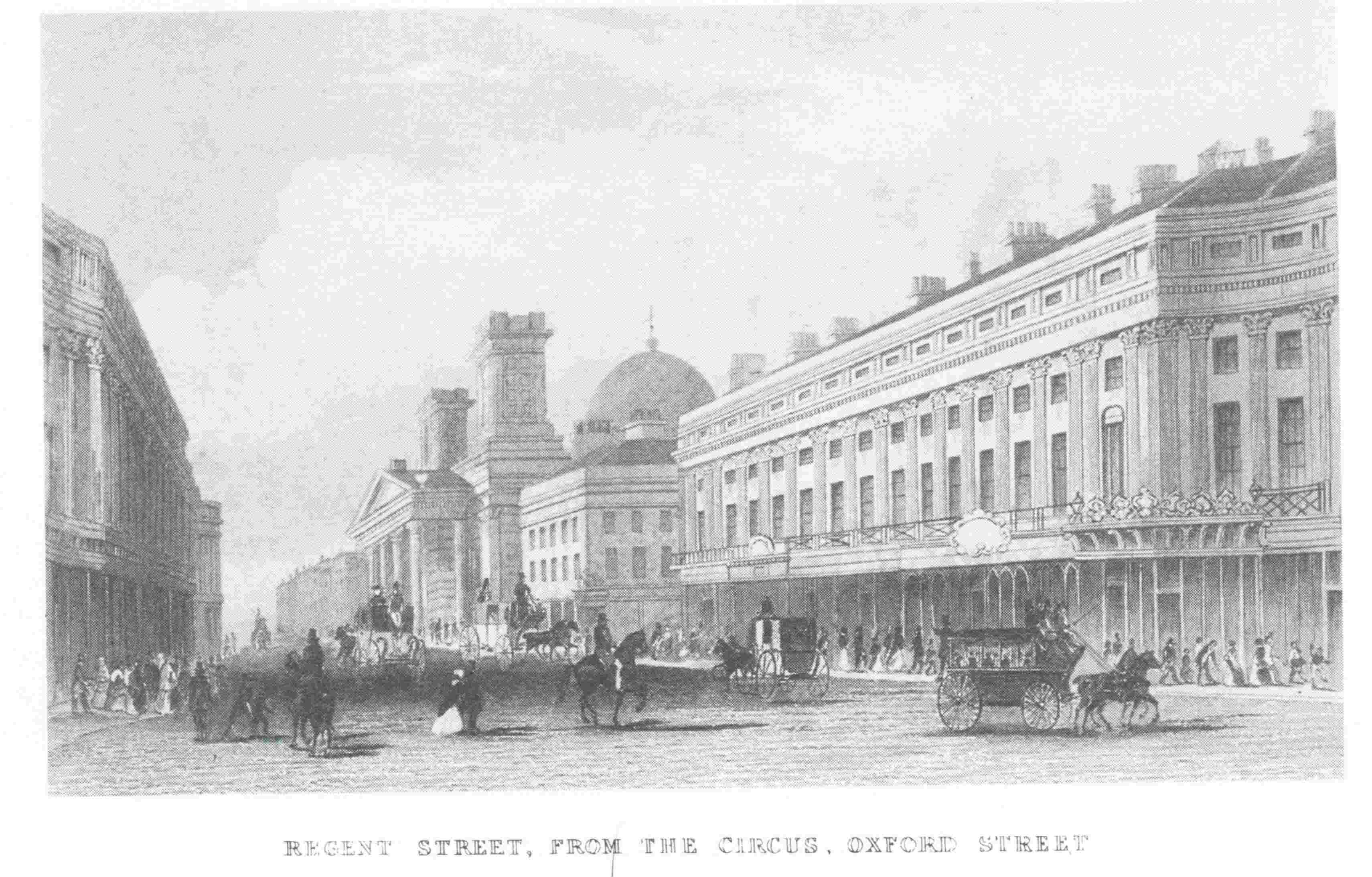

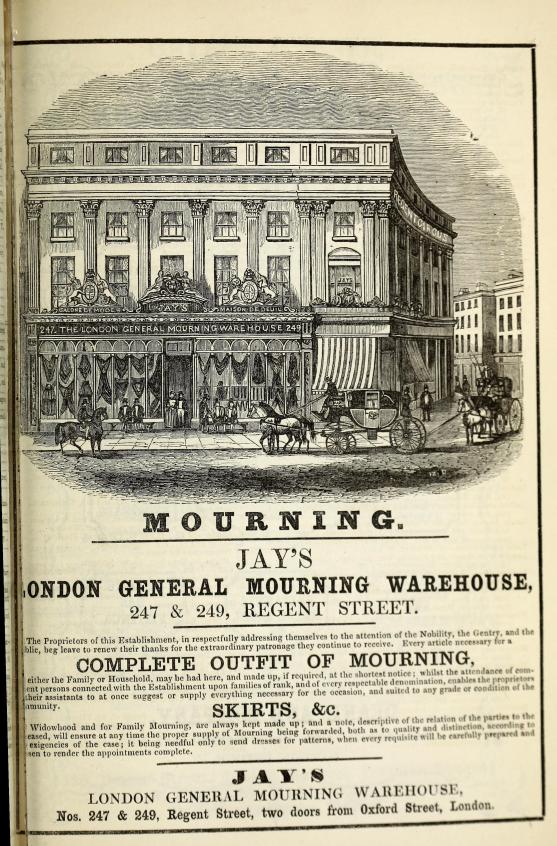

Demands made on dress and mourning ephemera resulted in a booming industry in mourning houses, or huge department stores specialising in mourning wear; often with a side-line in the import of exotic furs or similar. One of the largest and most renowned of these was Jay’’s Mourning Warehouse which opened on London’s Regent Street in 1841 and flourished for several decades, well into the 20thcentury. At its largest, Jay’s took up an enormous chunk of Regent Street, spanning several large units.

According to London Street Views, Jay’s initially began as a modest shop dealing in shawls at 217 Regent Street. They expanded quickly, with the Street Views archive page reporting that-

‘In 1847, Jay’s were still ‘only’ occupying numbers 247 and 249, but they eventually spread out over almost the whole section of shops on the west side of Regent Street between Princess Street and Oxford Street, from 243 to 251, just missing out on numbers 239 and 241.’

Jay’s were at the forefront of the profitable movement, leading the London mourning scene alongside Peter Robinson’s Mourning warehouse. By 1855, several other large mourning warehouses had sprung up on the same street as Jays’, hoping to cash in on their success. Due to the superstition of not holding mourning clothing in the household for longer than necessary, when a death occurred, you needed to act fast – places like Jay’s catered to this on a massive scale.

Through the catalogues and advertising handouts that remain, we can see that Jay’s not only prided itself in its quality of fabrics, but also on its ability to remain ‘on trend’.

Commenting on the shop’s fashion-forwardness, Henry Mayhew observed that

‘…our sackcloth must be of the finest quality… our grief goes for nothing if not fashionable.’

Similarly, they were keen to state that they kept up with all continental fashion trends in their mourning wear, writing that

‘It continues fashionable to wear mourning […] fashion in design, construction, and embellishment may be said to change, not only every month, but well-nigh every week.’

And also that, ‘To secure the very best goods, and to have them made up in the best taste and in the latest fashion, is one of the principal aims of the firm.’

Jay’s Mourning Warehouse also included suggestions of appropriate dress for the various degrees of mourning one might encounter in the back pages of its catalogues. This went through the family hierarchy and even provided suggestions for ‘affordable’ mourning attire for servants.

As a lady of good repute, there were several avenues one could take when dressing for mourning. Jay’s catalogue suggested that-

‘Ladies living at a distance may be supplied at their own Residence’ with an army of ‘experienced dressmakers and milliners , ready to travel to any part of the kingdom, free of expense to purchasers, when the emergencies of sudden or unexpected Mourning require the immediate execution of mourning orders.’

These travelling salesmen of sorts would be armed with fabric swatches and an array of ready made dresses and hats.

For other circumstances, there was a catalogue service available with several illustrated plates of dresses and accessories; Victorians loved catalogues, and Jay’s were very much the Argos of grief.

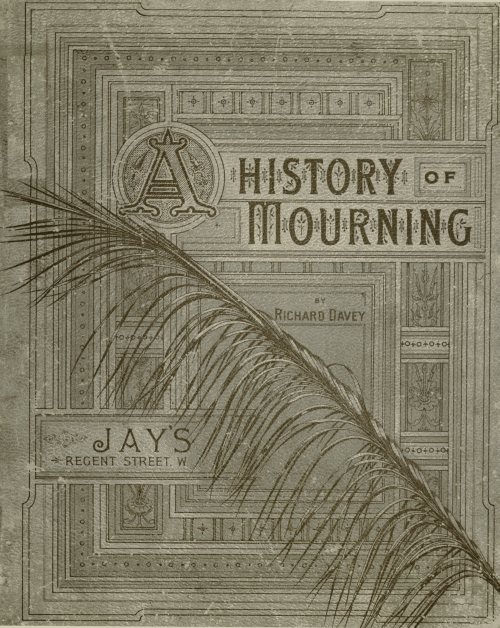

Jay’s were a veritable advertising behemoth and literally wrote the book on mourning. Well, they commissioned it at least.

Jay’s commissioned writer Richard Davey to write ‘A History of Mourning,’ a large and elaborately illustrated tome documenting mourning ritual from ancient Egypt to ‘present’ day. Davey explored not only clothing, but funeral rites and the mourning performances of the aristocracy throughout time. As Jay’s was primarily a business, and not in the realm of unbiased publishing, Davey’s work primarily focuses on the grief of the upper classes. Rituals surrounding deaths such as these were more likely to include the perceived necessity of expensive and elaborate clothes, jewellery and public performance. In showing their prevalence through time, Jays could adapt them to the contemporary masses.

If the Victorian reader was unsure as to mourning policy and guidelines, Davey helpfully included a series of notices toward the back of the book which offer detailed information as to what to wear, depending on your stage of grief.

While knowledge of appropriate mourning attire is presumed from all readers of court notices (appropriate mourning is often referred to as ‘decent.’), many notices included within Jay’s publication are more thorough.

On December 16th1861, the British Empire was plunged into mourning for The Prince Consort (Prince Albert). Subsequently, an order for court visitors to immediately enter mourning was published.

‘A History of Mourning’ includes regulations for the ‘ladies attending Court to wear black woollen Stiffs, trimmed with Crape, plain Linen, black Shoes and Gloves, and Crape Fans.’ Later, secondary notices include variations on fabric and the inclusion of ‘pearls, diamonds, or plain gold or silver ornaments.’

While those attending court were a tiny number, mourning was as much a class issue as it was a grief one. While we’ll explore class and social necessity in mourning another day, it must be mentioned that often, lower classes would mimic the mourning practises of the upper classes. The middle classes would mimic the ways of the upper classes, so to appear closer to high society. Lower classes would mimic upper classes and so on and so forth.

Naturally, Jay’s is held as the pinnacle of contemporary mourning, and documented in a considerable and favourable light. The business is described as –

‘…unique both for the quality and the nature of its attributes. Of late years the business and enterprise of this firm has enormously increased, and it includes not only all that it necessary for mourning, but also departments devoted to dresses of a more general description, although the colours are confined to such as could be worn for either full or half mourning.’

Considering the size of Jay’s at the time of publication, their range of departments is undisputed. Subsequently, the amount of staff required to run such an enormous business would be enormous. In the 1851 census, alongside William, his wife and five children (Thomas,Elizabeth, Ellen, Ada and Eugene), 20 staff members are also recorded as residing above the shop. The occupations of Jay’s residents varied from housekeeper to milliners and porter, and all resided beside the furs and mourning crape of the Jay’s machine.

Jay’s not only supplied clothing to the masses, after all, many small tailors and dressmakers could accommodate those needs with ease. Jay’s however, provided clothing and all mourning accoutrements for the household. From shoes to flowers and drapes, Jay’s was a one-stop-shop for all things grief-driven.

Jay’s arguably most famous patron was Queen Victoria herself who embodies and ultimately sculpted the national approach to mourning and grief during her reign. After the death of her husband, Jay’s dressed Victoria for the following 40 years.

When Jay’s own founder, William Chickhall Jay, died in 1888, he left an estate of around £100,000; an enormous sum at the time. Despite this enormous wealth and success, Jays is no longer a national stalwart and their old shop space has been filled with modern names. Jay’s traded well into the 20thcentury, diversifying their business into jewellery and other non-mourning wearables.

William Chickall Jay was buried at Kensall Green alongside three children who failed to reach adulthood.

While mourning fell out of favour with the turn of the century and the advent of the first world war, Jay’s is still held up today as the ultimate example of peacocking and triumphant, deathly consumerism in 19th Century mourning practise.

References/Sources

A History of Mourning by Richard Davey (1899) [Personal Copy]

https://londonstreetviews.wordpress.com/2013/09/12/jays-mourning-warehouse/

https://commercialoverprints.com/w-c-jay-co-jays-ltd/

https://lilacandbombazine.wordpress.com/2018/08/03/mourning-warehouses-and-where-to-shop/

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O59234/dress-fabric-and-peter-robinsons-mourning/

http://www.victorianweb.org/art/costume/mourning/8.html

Leave a comment